This is a guest post written by Nick Janetakis. It originally appeared on his blog, and has been published here with his permission. Nick is a self-taught full-stack developer and teacher, and has created a course for Docker beginners called Dive into Docker.

Visualize and understand the difference between how applications run in both Virtual Machines and Docker Containers.

The first thing you need to know is, Docker containers are not virtual machines.

Back in 2014 when I was first introduced to the concept of Docker containers, I related them as to being some type of lightweight or trimmed down virtual machine.

That seemed pretty cool on paper and the comparison made sense because Docker’s initial marketing heavily leaned on it as something that uses less memory and starts much faster than virtual machines.

They kept throwing around phrases like, “unlike a VM that starts in minutes, Docker containers start in about 50 milliseconds” and everywhere I looked, there were comparisons to VMs.

So, once again: Docker containers are not VMs, but let’s compare them.

Understanding Virtual Machines

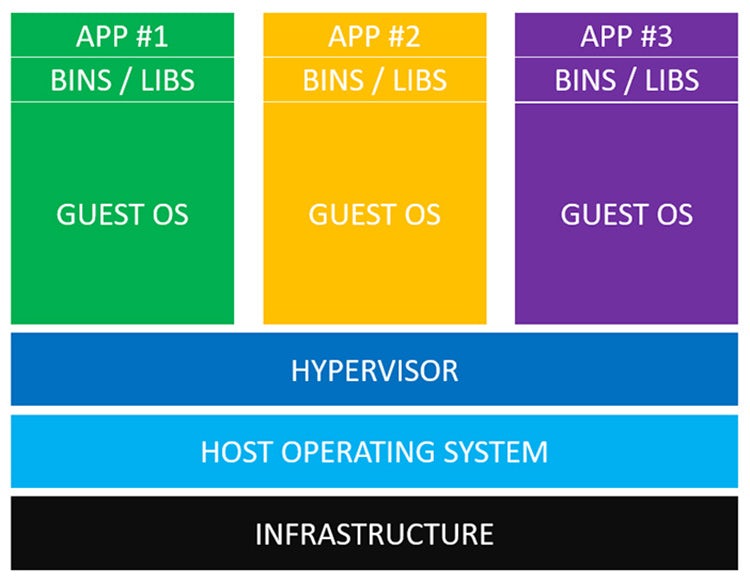

Here’s what it looks like to run a few apps on a server using virtual machines:

Now let’s define those layers from the bottom up:

–It all begins with some type of infrastructure. This could be your laptop, a dedicated server running in a datacenter, or a virtual private server that you’re using in the cloud such as DigitalOcean or an Amazon EC2 instance.

–On top of that host runs an operating system. On your laptop this will likely be macOS, Windows or some distribution of Linux. When we’re talking about VMs, this is commonly labeled as the host operating system.

–Then we have a thing called a hypervisor. You can think of virtual machines as a self contained computer packed into a single file, but something needs to be able to run that file. Popular type 1 hypervisors are HyperKit for macOS, Hyper-V for Windows and KVM for Linux. Popular type 2 hypervisors are VirtualBox and VMWare. That’s all you need to know for now.

–The next layer in this delicious server onion are your guest operating systems. Let’s say you wanted to run 3 applications on your server in total isolation. That would require spinning up 3 guest operating systems, which are all controlled by your hypervisor.

Virtual machines come with a lot of baggage. Each guest OS in itself might be 700 MB.

That means you’re using 2.1 GB of disk space just for your guest operating systems. It gets worse too because each guest OS needs its own CPU and memory resources too.

Then on top of that, each guest OS needs its own copy of various binaries and libraries to lay the ground work down for whatever your application needs to run. For example, you might need libpq-dev installed so that your web application’s library for connecting to PostgreSQL can connect to your PostgreSQL database.

If you’re using something like Ruby, then you would need to install your gems. Likewise with Python or NodeJS you would install your packages. Just about every major programming language has their own package manager, you get the idea.

Since each application is different, it is expected that each application would have its own set of library requirements.

Finally, we have our application. This is the source code for whatever awesome application you’ve built. If you want each app to be isolated, you will need to run each one inside of its own guest operating system.

That’s the story of running virtual machines on a server. Now let’s look at Docker containers.

Understanding Docker Containers

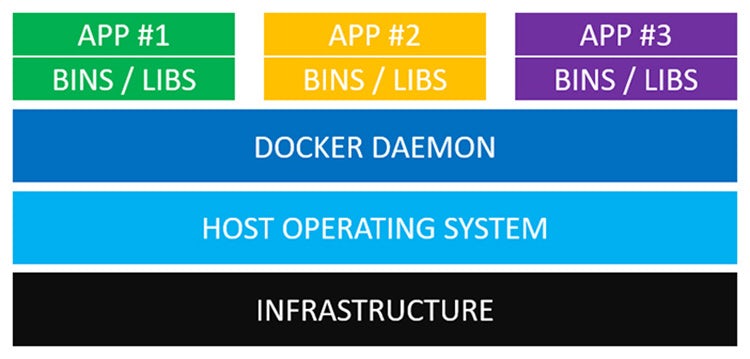

Here’s what the same set up looks like using Docker containers instead:

Right away, you’ll notice there’s a lot less baggage. You don’t need to lug around a massive guest operating system. Let’s break it down from the bottom up again:

Right away, you’ll notice there’s a lot less baggage. You don’t need to lug around a massive guest operating system. Let’s break it down from the bottom up again:

–Docker containers aren’t magic bullets. We still need some type of infrastructure to run them. Like VMs, this could be your laptop or a server somewhere out there in the cloud.

–Then, we have our host operating system. This could be anything you want that’s capable of running Docker. All major distributions of Linux are supported and there are ways to run Docker on macOS and Windows too.

–Ah, finally something new. The Docker daemon replaces the hypervisor. The Docker daemon is a service that runs in the background on your host operating system and manages everything required to run and interact with Docker containers.

–Next up we have our binaries and libraries, just like we do on virtual machines. Instead of being run on a guest operating system, they get built into special packages called Docker images. Then the Docker daemon runs those images.

–The last piece of the puzzle is our applications. Each one would end up residing in its own Docker image and will be managed independently by the Docker daemon. Typically each application and its library dependencies get packed into the same Docker image. As you can see, each application is still isolated.

Real World Differences between Both Technologies

In case you didn’t notice, there are a lot fewer moving parts with Docker. We don’t need to run any type of hypervisor or virtual machine.

Instead, the Docker daemon communicates directly with the host operating system and knows how to ration out resources for the running Docker containers. It’s also an expert at ensuring each container is isolated from both the host OS and other containers.

The real world difference here means instead of having to wait a minute for a virtual machine to boot up, you can start a Docker container in a few milliseconds.

You also save a ton of disk space and other system resources due to not needing to lug around a bulky guest OS for each application that you run. There’s also no virtualization needed with Docker since it runs directly on the host OS.

With that said, don’t let this article jade your opinion of virtual machines. Both VMs and Docker have different use cases in my opinion.

Virtual machines are very good at isolating system resources and entire working environments. For example, if you owned a web hosting company you would likely use virtual machines to separate each customer.

On the flip side, Docker’s philosophy is to isolate individual applications, not entire systems. A perfect example of this would be breaking up a bunch of web application services into their own Docker images.