Config policies overview

On This Page

- Introduction

- Quickstart

- How config policies work

- Use the CLI with config policies

- Writing Rego policies using CircleCI domain-specific language

- Package and name

- Rules

- Define a rule

- Evaluation

- Enforcement

- Enablement

- Using pipeline metadata

- Config policies with parameterization and reusable config

- Example

- Policing config 2.1 constructs

- Allowlists vs banlists with parameterization

- Use sets and variables

- Testing policies

- Config policies and dynamic configuration

- Example policy

- Next steps

| The config policies feature is available on the Scale Plan and from CircleCI server v4.2. |

Use config policies to create organization-level policies to impose rules and scopes to govern which configuration elements are required, allowed, not allowed etc.

Introduction

Config policies allow you to create policies for governing CircleCI project configurations. In its strictest case, if a project configuration does not comply with the rules set out in the associated policy, that project’s pipelines cannot be triggered until it does comply.

CircleCI uses config.yml files to define CI/CD pipelines at the project level. This is a convenient way of developing and iterating quickly, as each pipeline can be made to meet the needs of the project as it grows. However, it can be difficult to manage and enforce organization-wide conventions and security policies. Config policies adds in this layer of control.

Config policy decisions are stored, and can be audited. This provides useful data about the pipeline definitions being run within your organization.

Quickstart

If you already have a CircleCI account connected to your VCS, and you would like to get started with config policies right away, check out the steps in the Create a policy how-to guide to get started.

The following how-to guides are available for config policies:

How config policies work

Config policies use a decision engine based on Open Policy Agent (OPA). Policies are written in the Rego query language, as defined by OPA. Rule violations are surfaced when pipeline triggers are applied.

Policies can be developed locally and pushed to CircleCI using the CircleCI CLI. Policies can be saved to a repository within your VCS. For more information see the Create and manage config policies page.

CircleCI uses the result of OPA output to generate decisions from policy executions. Those decisions have the following outputs:

status: PASS | SOFT_FAIL | HARD_FAIL | ERROR

reason: string (optional, only present when status is ERROR)

enabled_rules: Array<string>

soft_failures: Array<{ rule: string, reason: string }>

hard_failures: Array<{ rule: string, reason: string }>The decision result tracks which rules were included in the making of the decision, and any violations, both soft and hard, that were found.

Use the CLI with config policies

Using server? When using the |

Use the CircleCI CLI to manage your organization’s policies programmatically. Config policies sub-commands are grouped under the circleci policy command.

The following config policies sub-commands are currently supported within the CLI:

-

diff- shows the difference between local and remote policy bundles -

fetch- fetches the policy bundle (or one policy, based on name) from remote -

push- pushes the policy bundle (activate policy bundle)For example, running the following command activates a policy bundle stored at

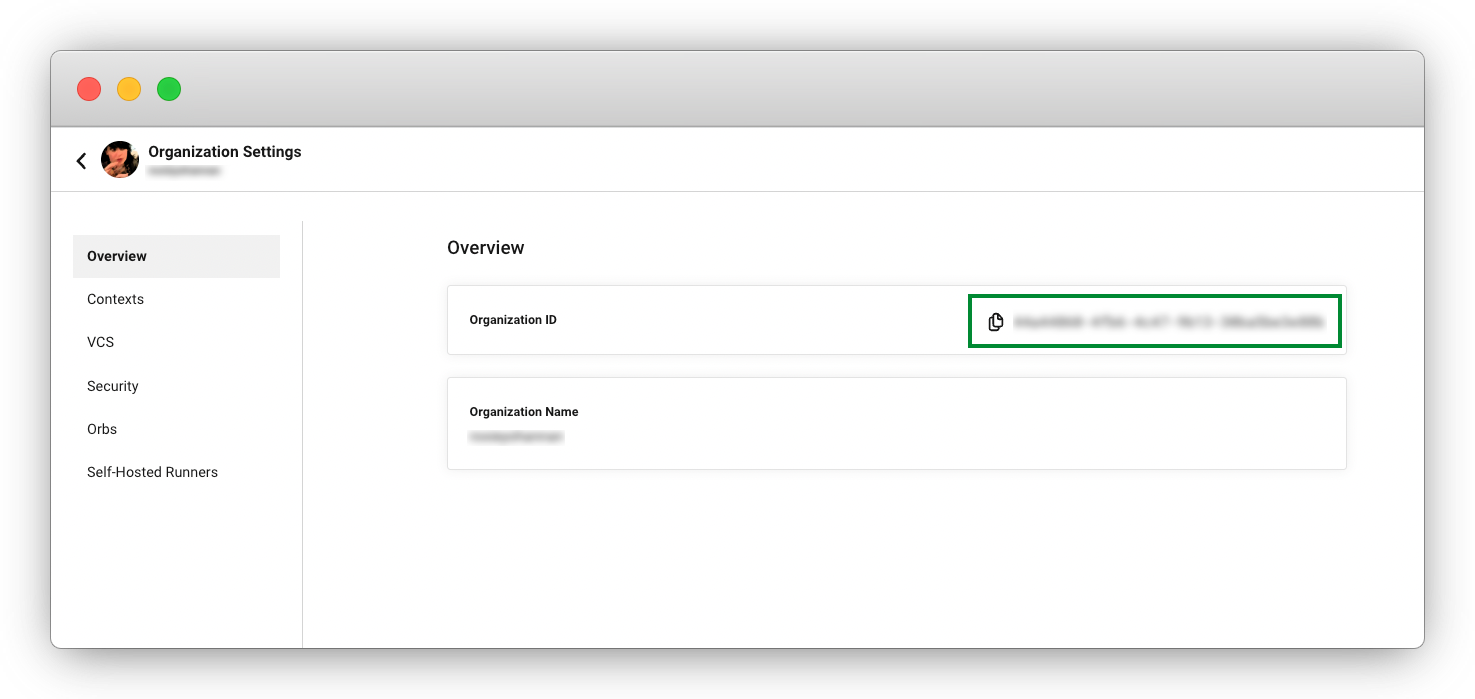

./policy_bundle_dir_path:circleci policy push ./policy_bundle_dir_path --owner-id <your-organization-ID> -

settings- used to modify config policies settings as required.When the

settingssub-command is called without any flags, current settings are fetched and printed on console.circleci policy settings --owner-id <your-organization-ID>Example output:

{ "enabled": false } -

test- used to run tests on your policies.For example, running the following command runs all defined tests in the

policiesdirectory:circleci policy test ./policiesExample output:

ok policies 0.001s 3/3 tests passed (0.001s)

To find your organization/user ID, select Organization Settings in the CircleCI web app side bar.

|

Writing Rego policies using CircleCI domain-specific language

Policies are written in Rego, a purpose-built declarative policy language that supports OPA. You can find more about Rego in the rego language docs.

In order for CircleCI to make decisions about your configs, it needs to be able to interpret the output generated when your policies are evaluated. Therefore, policies must be written to meet the CircleCI specifications detailed on this page.

Package and name

All policies must belong to the org package and declare the policy name as the first rule. All policy Rego files should include:

package org

policy_name["unique_policy_name"]The policy_name is an alphanumeric string with a maximum length of 80 characters. It is used to uniquely identify the policy by name within the system (similar to a Kubernetes named resource). Policy names must be unique. Two policies cannot have the same name within an organization.

The policy_name must be declared using a partial rule and declare the name as a rego key: policy_name["NAME"].

Rules

After declaring the org package and policy_name rule, policies can then be defined as a list of rules. Each rule is composed of three parts:

-

Evaluation - Evaluates whether the config contains the policy violation.

-

Enforcement status - Determines how a violation should be enforced.

-

Enablement - Determines if a policy violation should be enabled.

Using this format allows policy writers to create custom helper functions without impacting CircleCI’s ability to parse policy evaluation output. You can create your own helper functions, but also CircleCI provides a set of helpers by importing data.circleci.config in your policies. For more information, see the Config policy reference.

| Helpers in the context of config policies are rules like any other, but rules that are not individually enabled for the process of determining policy violation. Helpers can be written and used as building blocks for your policies. |

Policies all have access to config data through the input variable. The input is the project config being evaluated. Since the input matches the CircleCI config, you can write rules to enforce a desired state on any available config element, for example, jobs or workflows.

input.workflows # an array of nested structures mirroring workflows in the CircleCI config

input.jobs # an array of nested structures mirroring jobs in the CircleCI configDefine a rule

In OPA, rules can produce any type of output. At CircleCI, rules that produce violations must have outputs of the following types:

-

String

-

String array

-

Map of string to string

This is because rule violations must produce error messages that individual contributors and SecOps can act upon. Helper rules that produce differently typed outputs can still be defined, but rules that will be considered when making CircleCI decisions must have the output types specified above. For more information see the Enablement section below.

Evaluation

This is how the decision engine determines if a config violates the given policy. The evaluation defines the name and ID of the rule, checks a condition, and returns a user-friendly string describing the violation. Rule evaluations include the rule name and an optional rule ID. The rule name will be used to enable and set the enforcement level for a rule.

RULE_NAME = reason {

... # some comparison

reason := "..."

}RULE_NAME[RULE_ID] = reason {

... # some comparison

reason := "..."

}Here is an example of a simple evaluation that checks that a config includes at least one workflow:

contains_workflows = reason {

count(input.workflows) > 0

reason := "config must contain at least one workflow"

}The rule ID can be used to differentiate between multiple violations of the same rule. For example, if a config uses multiple unofficial Docker images, this might lead to multiple violations of a use_official_docker_image rule. Rule IDs should only be used when multiple violations are expected. In some cases, the customer may only need to know if a rule passes or not. In this case, the rule will not need a rule ID.

use_official_docker_image[image] = reason {

some image in docker_images # docker_images are parsed below

not startswith(image, "circleci")

not startswith(image, "cimg")

reason := sprintf("%s is not an approved Docker image", [image])

}

# helper to parse docker images from the config

docker_images := {image | walk(input, [path, value]) # walk the entire config tree

path[_] == "docker" # find any settings that match 'docker'

image := value[_].image} # grab the images from that sectionEnforcement

The policy service allows rules to be enforced at different levels.

ENFORCEMENT_STATUS["RULE_NAME"]The two available enforcement levels are:

-

hard_fail- If thepolicy-servicedetects that the config violated a rule set ashard_fail, the pipeline will not be triggered. -

soft_fail- If thepolicy-servicedetects that the config violated a rule set assoft_fail, the pipeline will be triggered and the violation will be logged in thepolicy-servicedecision log.

An example of setting the use_official_docker_image rule to hard_fail:

hard_fail["use_official_docker_image"]Enablement

A rule must be enabled for it to be inspected for policy violations. Rules that are not enabled do not need to match CircleCI violation output formats, and can be used as helpers for other rules.

enable_rule["RULE_NAME"]To enable a rule, add the rule as a key in the enable_rule object. For example, to enable the rule use_official_docker_image, use the following:

enable_rule["use_official_docker_image"]Use enable_hard to enable a rule and set its enforcement level to hard in a single statement.

The following statements are equivalent:

enable_hard["use_official_docker_image"]enable_rule["use_official_docker_image"]

hard_fail["use_official_docker_image"]Using pipeline metadata

When writing policies for CircleCI config, it is often desirable to have policies that vary slightly in behaviour by project or branch. This is possible using the data.meta Rego property.

When a policy is evaluated in the context of a triggered pipeline the following properties will be available on data.meta:

-

project_id(CircleCI Project UUID) -

build_number(number) -

ssh_rerun(boolean) - indicates if CI job is started using the SSH rerun feature -

vcs.branch(string) -

vcs.release_tag(string) -

vcs.origin_repository_url(string) - URL to the repository where the commit was made (this will only be different in the case of a forked pull request) -

vcs.target_repository_url(string) - URL to the repository building the commit

This metadata can be used to activate/deactivate rules, modify enforcement statuses, and be part of the rule definitions themselves.

The following is an example of a policy that only runs its rule for a single project and enforces it as hard_fail only on branch main.

package org

policy_name["example"]

# specific project UUID

# use care to avoid naming collisions as assignments are global across the entire policy bundle

sample_project_id := "c2af7012-076a-11ed-84e6-f7fa45ad0fd1"

# this rule is enabled only if the body evaluates to true

enable_rule["custom_rule"] { data.meta.project_id == sample_project_id }

# "custom_rule" evaluates to a hard_failure condition only if run in the context of branch main

hard_fail["custom_rule"] { data.meta.vcs.branch == "main" }The following is an example of a policy that blocks pull request builds from untrusted origins.

package org

import future.keywords

policy_name["forked_pull_requests"]

# this rule is enabled only if the body evaluates to true (origin_repository_url and target_repository_url will be different in case of a forked pull request)

enable_rule["check_forked_builds"] {

data.meta.vcs.origin_repository_url != data.meta.vcs.target_repository_url

}

# enable hard failure

hard_fail["check_forked_builds"]

check_forked_builds = reason {

not from_trusted_origin(data.meta.vcs.origin_repository_url)

reason := sprintf("pipeline triggered from untrusted origin: %s", [data.meta.vcs.origin_repository_url])

}

from_trusted_origin(origin) {

some trusted_origin in {

"https://github.com/trusted_org/",

"https://bitbucket.org/trusted_org/",

}

startswith(origin, trusted_origin)

}The following is an example of a policy that blocks SSH reruns on configs where a job uses sensitive contexts.

package org

import future.keywords

import data.circleci.utils

policy_name["ssh_rerun"]

enable_hard["disallow_ssh_rerun"]

sensitive_contexts := { "secops", "deploy_keys", "access_tokens", "security" }

disallow_ssh_rerun = "Cannot perform ssh_rerun with sensitive contexts" {

data.meta.ssh_rerun

some _, job in input.workflows[_].jobs[_]

count(utils.to_set(job.context) & sensitive_contexts) > 0

}Config policies with parameterization and reusable config

Writing policies for CircleCI version 2.1 configuration introduces some challenges due to the parameterization and reusable configuration options. To read more about these options, see the Reusable config reference guide.

Before executing any pipelines, config version 2.1 is compiled into config version 2.0. This compilation expands all parameters and reusable config blocks (jobs, executors, commands, orbs) into workflows and jobs.

To write highly effective policies, it is essential to reference the compiled version of the config (input.compiled).

Example

Consider the following example policy and configuration:

Policy

import future.keywords

policy_name["example_mistake"]

enable_hard["enforce_not_large_resource"]

# check every job in input config, and if any job has resource_class equal to "large" set a violation message.

enforce_not_large_resource[reason] {

some job_name, job in input.jobs

job.resource_class == "large"

reason = sprintf("job %s using banned large resource class", [job_name])

}Configuration with reusable executor

version: 2.1

executors: # Define reusable executor

lg-executor:

docker:

- image: my-image

resource_class: large # Resource class configured in reusable executor

jobs:

test:

executor: lg-executor

steps:

- checkout

workflows:

my-workflow:

jobs:

- testIn the above example, the policy is bypassed and will not trigger. The policy inspects jobs and does not find a resource_class == "large".

This is problematic because once the configuration is compiled, the job test will have a resource_class == "large".

Another way this policy could be unintentionally bypassed is by using parameters. Consider the following configuration, which uses a parameter to set the resource class for an executor:

Configuration using a parameter

version: 2.1

jobs:

test:

docker:

- image: my-image

parameters:

size:

type: string

resource_class: << parameters.size >> # parameterized definition of resource_class

steps:

- checkout

workflows:

main:

jobs:

- test: # invokation of parameterized job "test" with a size equal to "large".

size: largeThe same situation applies as for the first configuration presented above. The policy inspects the jobs and does not find a resource_class == "large", but instead finds << parameters.size >>, which is acceptable for the policy.

However, once the config is compiled, the job test will have a resource_class == "large".

To resolve both of these issues, it is important to acknowledge that we want to apply the policy to all jobs, which is a configuration version: 2.0 construct, and write the policy to target the compiled version accordingly, as follows:

Policy rule that inspects compiled configuration

# check all jobs in the compiled config and if any use a resource_class equal to "large" return a violation message.

enforce_not_large_resource[reason] {

some job_name, job in input.compiled.jobs

job.resource_class == "large"

reason = sprintf("job %s using banned large resource class", [job_name])

}Notice the rule now validates input.compiled.jobs. Regardless of parameters or reusable blocks (executors in this example), the policy is applied to all compiled jobs and functions as intended.

Policing config 2.1 constructs

Writing policies against config version 2.1 constructs (orbs, executors, jobs, commands) introduces the same parameterization challenges as described in the previous section. However, we cannot rely on writing policies against the compiled input because these constructs do not exist in configuration version 2.0.

Consider another example to illustrate this:

Policy to ban orbs from a specific namespace

import future.keywords

policy_name["example_mistake"]

enable_hard["ban_bad_orb_namespace"]

# check if any orb is namespaced with `bad`. If so, set a violation message for each of those orbs.

ban_bad_orb_namespace[reason] {

some key, orb_ref in input.orbs

startswith(orb_ref, "bad/")

reason := sprintf("orb %s is defined with a banned namespace: bad", [key])

}Configuration

version: 2.1

# top level pipeline parameters that can have a default set, or be modified by API based pipeline triggers.

parameters:

evil_orb:

type: string

default: bad/orb

orbs:

security: << pipeline.parameters.evil_orb >> # parameterized orb definitionIn the above example, the rule does not raise a violation because the string << pipeline.parameters.evil_orb >> does not have the bad/ prefix that the policy aims to detect.

We cannot rely on input.compiled because orbs are compiled away at that stage.

The best approach here is to detect if an orb reference is a parameterized expression and raise a violation accordingly. To do this we can use the is_parameterized_expression helper.

Policy to ban orbs from a specific namespace and detect parameterized orb references

import future.keywords

import data.circleci.config

policy_name["example"]

enable_hard["ban_bad_orb_namespace"]

# checks for orbs that are namespaced in "bad/" and set a violation for each orb.

# also detects and raises a violation for any orb defined with a parameter.

ban_bad_orb_namespace = { reason |

some key, orb_ref in input.orbs

startswith(orb_ref, "bad/")

reason := sprintf("orb %s is defined with a banned namespace: bad", [key])

} | { reason |

some key, orb_ref in input.orbs

config.is_parameterized_expression(orb_ref) # helper for detecting parameterized expressions.

reason := sprintf("orb %s is not allowed to contain a parameterized expression", ["key"])

}Allowlists vs banlists with parameterization

Policies and their rules can be categorized into two main types:

-

Allowlists: Assert that the input must match a specific value, or fall within a defined set of values

-

Banlists: Assert that the input must not match a particular value nor be within a set of prohibited values

When working with configuration version 2.1 constructs and parameterization, it is crucial to understand how these two rule types interact with your policies.

-

Banlist rules are susceptible to being bypassed using parameterization and reusable constructs. This is because the literal parameter value is unlikely to match the banned value, and during config compilation, the values intended to be banned can be reintroduced. All parameterization examples provided above fall into this category. To address this, you can either utilize

input.compiledor detect parameterization and handle it appropriately. -

Allowlist rules are incompatible with parameterization. They reject configurations that could otherwise be considered valid but do not cause invalid configurations to pass.

Consider an example to illustrate this:

This example is artificial and for illustration purposes only. The appropriate policy for enforcing job resource classes should target the compiled input (input.compiled). This ensures proper validation against the resolved values. |

Policy using an allowlist to restrict resource classes

import future.keywords

policy_name["allowlist"]

enable_hard["restrict_resource_classes"]

# check all jobs in config input and if the job is not "small" or "large" set a violation message.

restrict_resource_classes[reason] {

some job_name, job in input.jobs

not job.resource_class in {"small", "large"}

reason := sprintf("job %s must have resource class of small or large but has: %s", [job_name, job.resource_class])

}Configuration

version: 2.1

jobs:

test:

parameters:

size:

type: string

docker:

- image: my-image

resource_class: << parameters.size >>

steps:

- checkout

workflows:

main:

jobs:

- test:

size: smallThe rule (restrict_resource_classes) raises a violation because << parameters.size >> does not conform to the allowlist values of small or large. Even if this configuration would compile to a job that uses the correct small resource class, the violation is still triggered.

When working with allowlist-type rules, it is essential to recognize how they can restrict parameterization, so you can strike the right balance between configurational reusability and rule enforcement.

Use sets and variables

It is best practice to avoid hard coding values in code, and the same goes for your config policies. Hard coding data, such as project IDs, makes it difficult to read code, and can be confusing when collaborating with wider team members ("what is 99ada477-7029-44bb-b675-5b2d6448d1ab?"). Because using rego means your policies are defined in code, you can define sets and variables in rego files external to your individual policies, and reference these sets and variables across multiple policies. For an example of this in practice, see the Manage contexts with config policies page.

For further reading, see the Config policies blog post.

Testing policies

It is important to be able to deploy new policies with confidence, knowing how they will be applied, and the decisions they will generate ahead of time. To enable this process, the circleci policy test command is available. The test subcommand is inspired by the golang and OPA test commands. For more information on setting up testing, see the Test config policies guide.

The circleci policy test command is intended for testing the validity of the policy when adding and updating your config policies only within your config policy repo. Usage outside of adding/updating your config policy repo could result in false responses resulting from race conditions when reading and writing to the config policy service at the same time.

Config policies and dynamic configuration

You can write config policies to govern projects that use dynamic configuration too. Policies are evaluated against:

-

Setup configurations

-

Continuation configurations

-

Standard configurations

If required for your project, you can encode rules to apply only to setup configs, or only to non-setup configs, as follows:

enable_hard["setup_rule"] { input.setup } # only applied to configs with `setup: true`enable_hard["not_setup_rule"] { not input.setup } # only applied to configs that do not have `setup: true`enable_hard["some_rule"] # rule applied to all configsFor more information about dynamic configuration, see the Dynamic configuration overview.

Example policy

The following is an example of a complete policy with one rule, use_official_docker_image, which checks that all Docker images in a config are prefixed by circleci or cimg. It uses some helper code to find all the docker_images in the config. It then sets the enforcement status of use_official_docker_image to hard_fail and enables the rule.

This example also imports future.keywords, for more information see the OPA docs.

package org

import future.keywords

policy_name["example"]

use_official_docker_image[image] = reason {

some image in docker_images # docker_images are parsed below

not startswith(image, "circleci")

not startswith(image, "cimg")

reason := sprintf("%s is not an approved Docker image", [image])

}

# helper to parse docker images from the config

docker_images := {image | walk(input, [path, value]) # walk the entire config tree

path[_] == "docker" # find any settings that match 'docker'

image := value[_].image} # grab the images from that section

enable_hard["use_official_docker_image"]